The killing of George Floyd in 2020 was a low point for me. It summoned the ugly history of Black lynchings in the South in my mind. Although this level of racial terrorism has gone down significantly, these painful memories have been passed down through the collective history of African Americans and never forgotten. White America doesn’t always realize that the murder of Black men unjustly really wasn’t that long ago. For example, I grew up in the northeast U.S. I reconnected with my late grandmother’s extended family in Macon County, Georgia a few years ago. While there listening to relatives share the family history, I found out that a cousin of my grandmother was killed unjustly by a White man in the 1960s. He was never brought to justice. G. Terry is buried in the church’s cemetery with the rest of my recent ancestors with my slave ancestors buried nearby.

If you want to argue that Black men kill Black men more than the police. I agree but this isn’t the place to make this argument. I already know. If you want to argue that George Floyd was not murdered, this is also not the place. Although I researched the nuances of this story such as Floyd having fentanyl and methamphetamine in his system, kneeling on a man’s neck until he dies is overkill.

Minneapolis Police guidelines instructed officers on how to use certain neck restraints if a person was resisting arrest. According to the Associated Press, conscious neck restraint was for light pressure applied to the neck to help control a person without rendering them unconscious. An unconscious neck restraint is when officers could use their arms or legs to put pressure on arteries in the neck blocking blood flow to the brain rendering the person unconscious. This was used when a person was exhibiting aggressive behavior or actively resisting when lesser attempts had failed. However, neither neck restraint was designed for a knee on the neck although supervisors argued that this was within the realm of the policy. But to pin Floyd with a knee on his neck for 9 minutes and 29 seconds AND for the two other officers to be there including the four minutes after Floyd lost consciousness? The policy says that at the first possible opportunity, the person should be moved on their side when handcuffed and under control to avoid labored breathing that can lead to death. Floyd was never turned on his side, even as he said he couldn’t breathe 27 times before his body went limp.

I wrote the above simply to make the case that Floyd did not have to be murdered like that. This triggered my own bad memories of White men threatening me as a middle school student in a White section of Philadelphia.

After Floyd’s murder, graphic design work started pouring in from everywhere. What was my response? Before I tell you, briefly read about my graphic design experience.

My life in Graphic Design

I graduated from University of the Arts (which has since closed) in 1990 with a BFA in Graphic Design. At the time, its graphic design (GD) department was ranked near the top in the nation. I struggled in college with culture shock coming from a poor background and discrimination from a few of my professors. I started with 90 sophomores in the GD dept. and graduated with about 30 seniors. The program was rigorous and was often compared to getting a bachelors and a masters in 4 years. Although I received a world class education, I was very much stung by the favoritism and academic totalitarianism I experienced in the GD dept. For example, there was very little room to explore my own culture in relation to design although my Chinese and Greek classmates were encouraged to do so. I vowed to never return after I graduate. I was the first in my family to get a college degree and the first in the senior class to find a job (although it was never celebrated). I moved 1.5 hours west of Philly to a small town to work for an international non-profit.

Graphic design was a very White industry when I entered the field and it still is. American Institute of the Graphic Arts, (AIGA), our industry’s national trade association, hosted events in Philly. But I eventually stopped attending simply because I felt the frostiness as I tried to network and get to know others. (This happened in the 1990s. I doubled back in the 2010s to see if anything had changed. It had not IMHO. Read my comments in an article here.) Frustrated, I was glad to find Black mentors in other professions. In spite of this, I went on to become an award winning designer as my work narrowed to brand identity (logos, logo systems, etc.). I became known for working on urban and multicultural projects that involved audience research and a creative brief which determined design direction (logo, brand identity, marketing channels, etc.) Check out one of my case studies.

In 2016, the GD dept. at The University of the Arts (UArts) reached out asking me to speak at their 50th anniversary celebration. Although my heart had softened over the years, I ignored the email. Eventually one of the GD profs I liked reached out and invited me to lunch. I told him if I speak, I am telling the truth. He said, do it.

To test if anything had changed at UArts, I brought my then 13 year old son to the soundcheck and told him to simply observe. He knew about my college experience. We were dressed casual and walked into an auditorium with 5-7 other speakers waiting to soundcheck. My son and I said hello. Most turned around, looked us up and down and turned back around to continue chatting. I looked at my son, shook my head in amusement and sighed. The prof came to greet us and he went straight to my son making him feel welcome and greeted me as well. All of the sudden, the other speakers wanted to know who I was. Double sigh!

While speaking in front of design luminaries from around the world, I was tempted to give the GD department only accolades to boost my image. I shared how, back in the 2000s, I left the industry to infuse design principles into programs for poor children and youth in Wilmington, DE to increase their ability to interpret images. I taught elementary school students how to create their own alphabet in an afterschool program. (But I got in trouble when they passed around notes in class and the teacher could not decipher them. This was good trouble. Haha!) Considering that poor African American youth are heavy screen viewers compared to other ethnic groups, it was important to share what I learned with students growing up the way I did. (My friend Dr. Kristina Lamour Sansone has been studying this for years and has branded it Design Instinct Learning. She also graduated from UArts.) See her video below.

However, I reminded the anniversary attendees that even though I was rejected by the elitist design culture of the ivory tower, AIGA and design agencies, God showed me that the life he provided me to serve others was much bigger and rewarding than these design ghettoes. (Mentioning God is a radical statement around White designers who tend to be agnostic, atheist and/or new age.) After the event was over, a few people thanked me for giving the GD program a rose with thorns. I gracefully headed for the exit. A few shockingly asked, where are you going? I responded calmly and candidly, “Thank you for inviting me but no disrespect, you all are not my people. You all never wanted to be and I am okay with that.” Mic drop!!

DEI and George Floyd

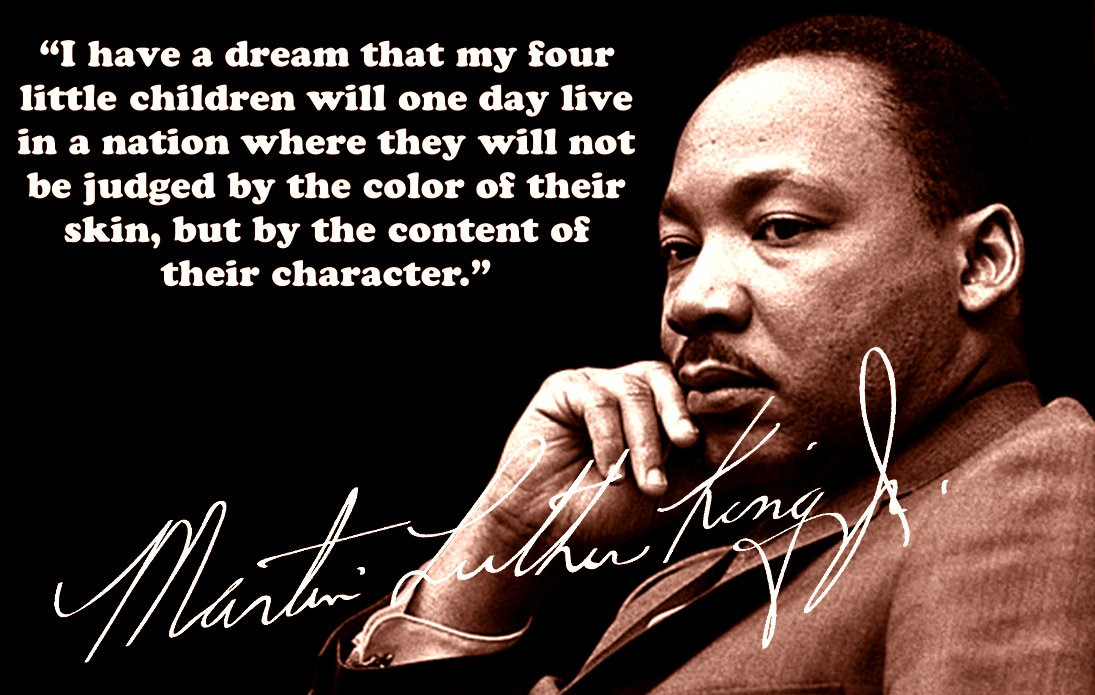

I am a supporter of Diversity, Equality and Inclusion but I have grave questions about Diversity, Equity and Inclusion. The DEI programs I benefitted from were about access and opportunity for anyone that was economically ddisadvantaged.This was MLK's dream. Today with Equality swapped out for Equity, many DEI programs prioritize group identity over individual merit. While in college in the late 1980s, I frequented the Act 101 office at UArts. This is a PA funded initiative for economically disadvantaged and educationally underprepared students. They provided mentoring to help me succeed through tutoring, academic advising and access to financial aid information. This program was crucial to my success since I had very little family support. Although this was not a DEI program, it helped a lot of Black students at predominantly white institutions (PWI) like UArts.

I remember discussions with many Black professionals in our 20s about the lack of mentors available for us in our professions. A big push through DEI programs in the 1990s was to mentore access to mentorship to Black students and professionals. It is very difficult to advance in any industry without a mentor. Although my friends eventually found them through DEI programs within their industries, I had to look outside of graphic design.

Flash forward to George Floyd’s murder. I am on Facebook and a part of an African American Graphic Designers Group. We all noticed design work materializing out of thin air for all of us. We had intense discussions about this.

There were three camps.

Camp #1 saw this as a form of reparations where people who benefitted from free Black labor over the centuries were able to give back. Camp #2 saw the work as exploitation and the goal was to look diverse. Camp #3 did not care. Money is money. I was in Camp #2. Our goal was not to limit each camp. It was to hear each other and see if it was possible to leverage this anomaly into a larger moment.

I received calls from three types of clients:

Companies bidding on large city Requests for Proposals (RFPs). These projects were required by the city to have a percentage of minority participation.

Design agencies bidding on regional non-city projects that required a percentage of minority participation from the client.

Academia wanting minority professors, lecturers and presenters so they can say they are woke.

I avoided #1, i.e., large companies that were known for exploiting their contractors. I don’t like working with people where everything is transactional with very little trust. I also avoided #3, i.e., opportunities to teach in colleges and universities. Mind you, I actually was an adjunct professor from 2010-2017 at Eastern University. I did a fair bit of writing about design on my website. I applied to teach courses at most universities in Philadelphia including UArts before George Floyd and all I heard was crickets. When everyone became woke after Floyd’s murder, I heard from colleges and universities asking me to teach that I applied to 5 years ago.

I did sit on a panel for Capstone projects for UArts Graphic Design seniors and I was shocked at the entitlement of some of the students. When offered constructive critique, if they did not like it, it was taken personally and rebuffed. I said I would never do that again.

When screening potential clients, I asked a series of questions that revealed their true intentions or their silence gave it away. Most of the time, I realized I was a token and I valued my integrity higher than this opportunity. I also felt fortunate that I was in the twilight of my career and had already carved out my own space in the design world. As the country grows more diverse, the advantage leans more in my direction anyway.

In conclusion, work started to drop off immediately around 2023. And once again, we (Black designers) conferred with each other. We were all experiencing it. None of the clients who initially contacted me for work darkened my email box again. I have no regrets. I prefer compassion over their pity. According to Psychology Today, compassion involves a far greater commitment compared to pity. Compassion means putting skin in the game. Pity is for spectators who want to feel sorry for you while maintaining a safe emotional distance. Compassion is used to help someone grow, not simply give them something to make the other person feel better.

In Luke 4:18-19, Jesus’ compassion is evident when he went into the synagogue, stood up and read from the scroll of the prophet Isaiah:

“The Spirit of the Lord is on me,

because he has anointed me

to proclaim good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim freedom for the prisoners

and recovery of sight for the blind,

to set the oppressed free,

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.”

Jesus is proclaiming the good news, freedom and recovery of sight for those who are experiencing shame because of their condition. Although I don’t expect a company to fully embody these principles, I would choose a client who really believes I bring valuable skills to the table over someone who wants to pacify me. If a potential client can show me how a project could not succeed without me, I am ready. However, most of the people who contacted me treated me like a lawn jockey. But my design work speaks for itself. (Click here to see my work.)

My goal in life is to embody compassion wherever I am and extend it to others. I have hired other designers and shared what I know. I wish the police officers would have showed more compassion for George Floyd. He might be alive today.

When thinking about DEI programs, I still cling to Martin Luther King, Jr’s dream for me, my four children and my grandson:

It's a shame it took George Floyd's murder for you and other black designers to see demand for your work. But it's unfortunately not surprising.

On equity vs equality - Do you think it's possible to practice equity with compassion rather than pity? If so, would that ever be appropriate in the workplace?

Depending on how you read 1 Corinthians 12:22-25, it seems like Paul may be advocating for some form of equity in the body of Christ. Would it ever make sense to practice it in church?